Originally posted on Medium, June 8, 2017.

What is Creativity? Why is it so important to have creativity in our practice as museum professionals? Questions like these two are what we ponder every day to fulfill our museums’ missions and our career goals. Creativity allows us to be able to express ourselves and provides another outlook on the world around us. Museum professionals especially need to express their creative sides to help their organizations continue to grow and adapt to their changing communities. This is not a new topic but we can always learn something new when we express our creative side. I learn a lot when I allow to express my creative side whether it is drawing, writing, or making projects; and I use my experiences inside and outside of museums to inspire me to create something different and sometimes the same subject from a different perspective.

Since I was young, I made various drawings of many things including animals and landscapes. As I developed my interests in museums, I began drawing museums I have been to and museums I have worked with. For instance, I drew the Butler-McCook House in Hartford, the Stanley-Whitman House in Farmington, Connecticut, Noah Webster House in West Hartford, and Connecticut Historical Society. I drew many of these drawings from my own memory, and one was drawn using a photograph as reference. Also, I used either pens or pencils to make my drawings (depending on which utensil was available at the time). I learned to use my creativity to assist in my museum experience, and I continue to use references from books and professional development programs discussing creativity.

Connecticut Historical Society, pen, drawn 2015

Connecticut Historical Society, pen, drawn 2015

Noah Webster House, pen, drawn 2015

Noah Webster House, pen, drawn 2015

Stanley-Whitman House, pen, drawn 2014

Stanley-Whitman House, pen, drawn 2014

Butler-McCook House, pencil, drawn 2014

Butler-McCook House, pencil, drawn 2014

One of the resources I used and continue to use is Linda Norris’ and Rainey Tisdale’s Creativity in Museum Practice to help me get inspired. Norris and Tisdale express the importance of allowing creativity to inspire work in the museum no matter which department they work from. In their book, they state that they believe “the daily life of museum workers behind the scenes both needs and deserves more attention in order for museums to reach their full potential.” Norris and Tisdale shared colleagues’ stories from across the museum field of what creative practices have worked for themselves and their museums. Also, they shared their own tips on how to jumpstart one’s creative practice using no-cost or low-cost activities. Throughout the book, Norris and Tisdale discuss many ways museum professionals can find creativity in their daily tasks, and use whatever inspiration they find in the environment they are surrounded by. The style of this book is written as both a textbook and a workbook to help museum professionals spark their own creativity.

Norris, Linda and Rainey Tisdale, Creativity in Museum Practice, Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2014.

Norris, Linda and Rainey Tisdale, Creativity in Museum Practice, Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2014.

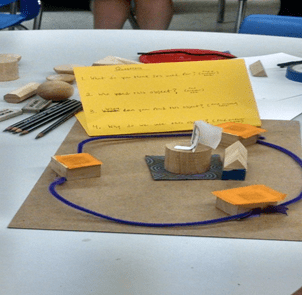

One of the professional development programs I participated in was a NYCMER workshop in October called “Exhibition Designs for Educators” at El Museo del Barrio. This program was an example of how educators can learn to express their creativity to design exhibits and programs simultaneously. There was a challenge in which we were not told what the object was, and we were expected to create an exhibit with an unknown artifact (what appeared to be a cement block). The group I worked with received the prompt to create this exhibit as a warm and friendly environment; we brainstormed various ways we could create the exhibit using the prompt. For more information about this activity, check out the post “Writing about Museum Education: Using Professional Development to Our Advantage.” By brainstorming together as a group, we were able to express our collective creative experience that led to the concept we designed.

“Exhibition Designs for Educators” Activity, October 2016

“Exhibition Designs for Educators” Activity, October 2016

Creativity is especially used in museum education programs to not only entertain its audiences but to educate them on the subject matter of the museums’ expertise including but not limited to art, history, and science.

There are many examples of when I used creativity as a museum education professional. For instance, while I was working in historic house museums in Connecticut, I taught and assisted participants in making crafts and cooking recipes for school and camp programs. One of the crafts I helped kids make were cornhusk dolls during the summer camp program at Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society which not only was a fun activity but they also learned about what kinds of dolls kids during the eighteenth century played with and created themselves to find ways to entertain themselves. I have also helped fifth grade students make apple pies and Irish-style mashed potatoes at the Stanley-Whitman House in Farmington. At Connecticut Landmarks Butler-McCook House, I helped kids create Samurai helmets out of gift wrap and yarn during the New Year’s Eve celebration, First Night Hartford. The Samurai helmet activity was inspired by the Samurai armor that the McCook family have in their old 18/19th century house; Reverend McCook and his daughter Frances traveled to many places on the way to and from China to visit another daughter Eliza, and one of the places they visited was Japan where he purchased the Samurai armor to bring back to Hartford.

One of the most recent examples include creating activities for kids to participate in during down time in school programs and during general tours at the Long Island Maritime Museum. I created activities such as cross word puzzles, word searches, matching games, and a scavenger hunt. To create these activities, I used information about the Long Island Maritime Museum and the maritime history it shares with its visitors. For instance, I created a crossword puzzle about one of the historic buildings on the museum’s property called the Rudolph Oyster House based on the information about the Oyster House and oyster business; the Rudolph Oyster House was built in 1908 by William Rudolph for his oyster company established in 1895, and it was used as an oyster culling and shucking house until 1947 and was acquired by the Long Island Maritime Museum in 1974.

Another example of activities I created was a breeches buoy search to teach participants the parts of the breeches buoy, an early contraption that pulled victims from shipwrecks, by writing down the names of the parts next to the corresponding letter (I included a word bank so they see the appropriate names). The next example of activities I created is a Name These Boats activity that challenges participants to use their memories of the boats stored in the museum’s Small Craft Building. I included a word bank to limit the possibilities, and participants would write down the name of the boat next to the photograph of a boat.

I also had the opportunity to observe a children’s program that the Maritime Explorium in Port Jefferson participated in. Children created sound-sandwiches for them to take home and play music on by blowing into them like harmonicas. The sound-sandwiches were made with tongue depressors, two pieces of straw, and rubber bands. To make them, one of the two tongue depressors needs a large rubber band wrapped around it from one tip to another; then the two tongue depressors and two small pieces of straw are tied together with smaller rubber bands at the ends. Sound-sandwiches can be adjusted until a humming or vibrating sound is heard. This was not only a fun activity for children to participate in but they also learned how to create sound by using the materials they were given.

Last weekend I created another exhibit for my childhood church to share the community’s summertime fun since the season would be around the corner soon and I wanted this exhibit to focus more on the parishioners as well as their interactions with the community around them. I included photographs from the Summer Festival the church participated in in 1975, and photographs from a Church picnic that took place by the beach in the 1960s. I also included bulletins that included announcements of activities planned for the summer, ways to get involved in the community, and current events to remind parishioners to be good Christians and learn more about the issues discussed as a result of events. I designed little suns to decorate the exhibit with to represent summer. This exhibit is an example of how creativity is especially useful during the exhibit design process.

Summertime Fun with Trinity exhibit, opened June 4, 2017

Summertime Fun with Trinity exhibit, opened June 4, 2017

Tomorrow I am also participating in another professional development program about creativity, Creativity Incubator. It is a New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA)/ Greater Hudson Heritage Network (GHHN) Partnership Program which encourages museum staff to test out experimental interpretive approaches through hands-on activities. I will travel to the Raynham Hall Museum in Oyster Bay, New York where it is being hosted. Creativity will continue to be a significant part of our work as museum professionals, and we need to find ways to inspire creativity in our work and inspire creativity with our visitors.

What ways have you found to inspire creativity work for you? Do you have a favorite moment where you accomplished a creative project, museum-related or not? Have you been inspired by something outside of the museum field that helped you complete a project?