Originally posted on Medium, April 6, 2017.

After a while, I have completed Hugh H. Genoways and Lynne M. Ireland’s Museum Administration 2.0 with revisions made by Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko. It took me a while to read this book because I wanted to make sure I comprehended each detail the authors provided. I wanted to read this book not only develop my skills as a museum professional but to learn more about how museum administration works. As a museum educator, in the past, I had limited experience in the administration aspect of the museum. I taught school and public programs and the experiences I gained did not include a lot of administration skills. The administration skills I gained before I went to the Long Island Museum was some time answering phone calls and preparing flyers and mailings.

While I was at the Long Island Museum, I gained more administration skills that helped me develop my skills as a museum professional. In addition to teaching school programs and implementing public programs, I learned how to book school and group programs including tours and In the Moment program (for Alzheimer’s/dementia patients); after answering phone calls and taking down information such as the name of school/organization and the number of individuals attending, I recorded the information on the facilities sheet, placed the program and organization (as well as the time) on the Master Calendar via Google Docs, and provide the program/school/organization/time information on the daily sheet to write down official numbers as well as observe the number of programs for that day.

Also, I was also in charge of scheduling volunteers who taught larger school programs that require various stations and geared towards larger school groups. Based on how many of these school programs were scheduled for that month, I used the sheet of the volunteers’ availability to schedule the number of volunteers needed to run the program(s) for the number of days scheduled. Once finalized I printed copies and sent them to all volunteers while keeping one to put on the board for them to refer to while at the museum.

In addition to the programming related administration work, I also worked on various projects in the Education department. For instance, I oversaw printing program flyers, after the everyone in the department approved of the details, and sending the flyers to the head of the Suffolk County and Nassau County libraries for them to distribute to all libraries in the counties to post on bulletin boards; I also made sure there was many copies printed to be sent to and distributed at the museum’s visitor center. Then I went over budgets with the Director of Education for purchasing food and drinks for the public programs; we collaborated on the paperwork once the items were purchased. Also, I made sure the mailing for school program brochures and bus trip flyers mailings went smoothly; I printed address labels, placed address labels on envelopes, placed brochures/flyers in the envelopes, borrowed mailing boxes from postal offices to place envelopes in, and send them to the post office to be mailed. Since the Long Island Museum, I answered and redirected phone calls at the front desk, assisted in gift shop inventory, and tallied volunteers’ sailing Priscilla records during last year’s sailing season at the Long Island Maritime Museum.

I decided to write a review of this book because not only will this book be useful for all museum professionals but it has also been a while since I wrote a book review. By reading this book, I gain a deeper understanding of the museum running process on all levels and I hope everyone who reads this blog entry will also have a better understanding of how museums are run.

Genoways, Hugh H., Lynne M. Ireland, Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, Museum Administration 2.0, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. ISBN: 978–1442255517

Genoways, Hugh H., Lynne M. Ireland, Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, Museum Administration 2.0, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. ISBN: 978–1442255517

This book is a second edition to the Museum Administration book published in the early 2000s and revisions were made in this second edition to provide updates on changes in the field since the first edition was published. The authors pointed out that this book is not just for museum directors and department heads but this book is for all members of the museum staff who have administrative duties. The book also provided not only case studies and case reviews but it also shared activities that can be used to practice the skills introduced in that chapter. There are also diagrams to illustrate the concepts explained in the chapters. Also, the authors pointed out the main point of this book which is this book should be used as a quick reference, inspiration during challenging times, and a jumping off point to dig deeper into more complex topics. Each chapter is dedicated to different aspects of how museums are run from what a museum and administration is to interpretation, exhibits, and programming.

The first chapter not only defines what a museum is and what an administration is but it also discusses types of museums, museum associations, the museum profession, and academic programs related to the field. In this chapter, the academic programs discussed in the book are museum studies, public history, and archival education. The chapter also lists several museum associations that exist in the United States including the primary professional museum association American Alliance of Museums, American Association for State and Local History, Association for Living History, Farm, and Agricultural Museums, Association of Children’s Museums, International Museum Theatre Alliance, and Museum Education Roundtable. The first chapter also pointed out that ultimately when learning about administration in museums experience is the great teacher. Also, it is important to know that no matter what position one holds in the museum each staff member will be expected to perform some administrative duties and each day presents sets of opportunities to make something happen.

The second and third chapters discussed start up and strategic planning. According to the second chapter on start up, creating a new museum or improving an existing one is a complex process requiring a clear sense of purpose and compliance with state and federal regulations. A couple of things the chapter points out are a museum should form only when a community can specify the need for it and plan a solid business model for its sustainability; and all museums need a well-defined mission statement, written bylaws, articles of incorporation, and IRS tax-exempt status. Another important part of museum operations is strategic planning; a strategic plan is a map or chart an organization agrees to follow for three to five years to reach its goals, and the plans are strategic when the goals that respond to a museum’s environment, seek a competitive edge, effectively serve stakeholders, and identify the keys to long-term sustainability.

There are ten steps in the developing process of a strategic plan for a museum. The steps are initiate and agree on process, identify organizational mandates, identify and understand stakeholders and develop mission, external and internal assessments, identify strategic issues, review and adopt strategic issues, formulate strategies (action or work plans) to manage strategic issues, establish a vision for the future of the museum, evaluation and reassessment, and finalizing the plan. The fourth and fifth chapters discuss topics on finance and sustainability.

I appreciate that the finance chapter went into such detail since finance is important for the staff to have a handle on how money is spent as this helps them make effective decisions with significant financial impact. The chapter discusses how to develop a budget, manage a budget, and accounting. Budget management requires both a day to day approach and a long view so by learning all the steps of developing and maintaining the budget a museum will be able to function and fulfill its mission. On the chapter of sustainability, it discusses how a museum’s financial stability and future rely on effective fundraising and revenue-generating practices that provide for present operational needs and generate income for future capital and operational needs.

There are various parts of financing that help sustain museums to keep them running. For instance, development is about building relationships with people that would lead to the end result (money) for museums. Other parts of sustainability include making a (development) plan, raising funds, accumulate contributed income (i.e. memberships, annual giving, sponsorships, fundraising events, and campaigns), planned giving, government support, and grants. Museums are also sustained through earned income which includes admission fees, museum store, dining facilities, planetariums and theaters, educational programming, special exhibits, traveling exhibits, and blockbuster exhibits and other partnerships.

The sixth and seventh chapters discuss topics on the working museum and ethics and professional conduct. According to the working museum chapter, staff are the museum’s most valuable asset. I agree with this statement because each museum staff member has a role in keeping a museum running, and a museum like any organization is like a car (each part of a car helps keep the car running and performing its functions as well as fulfilling its purposes). The working museum describes how the staff, board members, and volunteers understand how their organization is laid out in chart form that would be especially helpful for new people joining the organization. It also discusses the museum employees which reveals general expectations of the employee based on their job descriptions, and the significance of leadership in museums with detailed descriptions of leadership types. This chapter also went into detail about how the museum board, director, and staff should interact with one another.

In the ethics and professional conduct chapter, it points out that there is a universal agreement that standards articulate a way to guide the thoughts and actions of museum professionals and provide some basis for judging the performance of institutions and individuals. The chapter discusses museum ethics by defining ethics and how important it is to develop a code of ethics for museums. Also, the chapter describes ethics statements and a good statement according to the authors will articulate the traditional values or morals and communal standards of the museum profession. Then the chapter discusses the codes of professional museum conduct through governance, collections, institutional codes of professional museum conduct, and enforcement.

The eighth and ninth chapters talk about legal issues and facilities management. I appreciate that in the beginning of the legal issues chapter the authors stated that nothing in the chapter should be considered legal advice because it reinforces the idea that this book should be used as a reference. The authors also recommended a couple of books to use as museum law references to start with and then seek legal counsel when necessary: Museum Law: A Guide for Officers, Director and Counsel by Marilyn E. Phelan (2014), and the 2012 update of A Legal Primer on Managing Museum Collections by Marie C. Malaro and Ildiko P. DeAngelis. This chapter provides brief detailed descriptions of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Unrelated Business Taxable Income (UBIT), legal liability, artists’ rights, copyright, and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. To have a good facilities management plan, museum staff must consider the needs of the people who work within the organization, the preservation and exhibition of objects in the museum’s collection, and the people who visit the museum.

The facilities management chapter describes in detail museum facilities and the significance of maintaining the museum property. Museum facilities includes the physical structure and the utility services. This chapter also discusses facility operations which includes housekeeping, emergency preparedness, health and safety, fire prevention, safety data sheet, hazardous materials, biological waste materials, integrated pest management, and security. Visitor services is also part of facilities management since providing a range of services will make the museum a welcoming environment for visitors to feel comfortable in and a guaranteed return visit. The services provided are pre-visit information, parking, accessibility, orientation, museum stores, rest rooms, food service, and educational services. In the tenth and eleventh chapters, the authors provided details on marketing and public relations as well as collections stewardship.

Both marketing and public relations are married concepts since both concepts deal with communications and reaching to the public. Marketing is a process that helps people exchange something of value for something they need or want. This chapter discusses several aspects of marketing including motivations for marketing, history of marketing activities, the marketing plan, tactical marketing, and e-communications. Public relations, meanwhile, is built upon marketing and is charged with trying to develop a successful image for the organization. The chapter also discuss how public relations are incorporated in museum’s overall strategic plan; it also describes the PR tools museums use in museums’ public relations practices which are events, community relations, media relations, media releases, public service announcements, interviews and speeches, print materials, and buzz. This chapter also discusses the significance of museums and the community working together to maintain museums’ relevance within the community. The authors dedicated an entire chapter on collections stewardship.

In this chapter, the authors describe what a collections management policy is and addresses nine issues that the collections management policies must cover. The nine issues mentioned are collection mission and scope, acquisition and accessioning, cataloging, inventories, and records, loans, collection access, insurance, deaccession and disposal, care of the collection, and personal collecting. Each of these nine issues are fully described throughout the chapter. The twelfth chapter discussed interpretation, exhibition, and programming.

According to the book, interpretation is everything we do that helps visitors make sense of our collections include: exhibitions, education programs, and evaluation. The core of interpretation is communication and it is up to museum professionals to translate these communication pathways to a variety of audiences. In this chapter, it discusses exhibits as well as interpretive planning, exhibit policy, exhibit planning and development. The chapter also went into detail about programming as well as the policy and guidelines for the museums’ educational functions. All museums also need to provide evidence from outcome based evaluations that they are fulfilling the social contract of providing educational experiences for its visitors.

One of the things that we all should take away from this book is the longer one works in the field, the more one will know and the more one will give back to the field. The advice that I took away from this book is to keep your head up, your eyes forward, and your brain learning. This is important to me as a museum professional because I understood that we are always learning from our experiences and we continue to develop our skills as museum educators to better serve our institutions and our communities. While I read this book, I used a pencil to write down notes in the books to highlight the main points of the book for whenever I want to look back at the lessons this book presented. It is an important book I will continue to use throughout my career as a museum professional.

What are your experiences in museum administration? How have you applied your administrative skills in your daily role as a museum professional?

Samis, Peter and Mimi Michaelson, Creating the Visitor-Centered Museum, New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

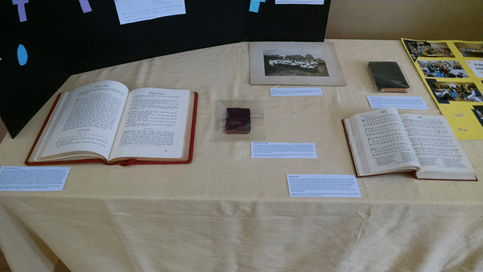

Samis, Peter and Mimi Michaelson, Creating the Visitor-Centered Museum, New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017. Some of the items selected for the exhibit.

Some of the items selected for the exhibit. Picture of exhibit board designed using limited resources.

Picture of exhibit board designed using limited resources. The exhibit as a whole. Trinity Traditions: Easter Celebrations Throughout the Century.

The exhibit as a whole. Trinity Traditions: Easter Celebrations Throughout the Century. Genoways, Hugh H., Lynne M. Ireland, Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, Museum Administration 2.0, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. ISBN: 978–1442255517

Genoways, Hugh H., Lynne M. Ireland, Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, Museum Administration 2.0, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. ISBN: 978–1442255517