Originally posted on Medium, April 20, 2017.

This week I thought I would discuss the video I watched of the discussion with Kimberly Drew, Social Media Manager at the Metropolitan Museum, through the MuseumHive broadcast that aired last week. MuseumHive is an informal hangout of people, created by museum media developer Brad Lawson, connected with museums to explore new community-centered visions for museums. It uses Google Hangouts to both create content and encourage people to socialize on the Internet and in person (museum professionals gather at the Roxbury Innovation Center in Boston). To learn more about MuseumHive and its programming, visit http://www.museumhive.org . According to MuseumHive, Kimberly Drew is a leading thinker in the museum world focusing on black culture and art, and has a wide range of articles written about her work including “4 Black Women Making the Art World More Inclusive” in New York Magazine. Her practice is at a cross between contemporary art, race, and technology. Drew’s practice can be described as a place for those who would be negated access and space, and is an inverted version of what already exists rather than oppositional.

Before reviewing the video, I read a blog post on the MuseumHive website about this discussion. One of the quotes from Drew used in the blog caught my attention:

“I think about the things I’m sending out in the world because there are so many silences within the web and in the truth of our particular moment. I try to think about the things that I send out, can create, or can share, and how I could share positive images and also real images and also be able to articulate history in a way that feels inclusive…When you’re adding to this noise, in what ways are you improving upon silence?”

— Kimberly Drew, The Creative Independent

This quote resonated with me because as a museum professional who uses social media to share her experiences on and to express her thoughts about the field I also try to both share positive messages and share real information that is inclusive for readers out there both in the museum professional field and in other fields respectively. In the discussion video, Drew talks about her work in social media and about technology in the museum field.

The style of the video was a Question and Answer session between hosts, members in the audience, and Drew. One of the first questions Drew answered was how she got her start in social media career. Drew explained that she was bouncing around various smaller art organizations before she started working at the Met where she has been working for the past two years. She began her career with an internship in the Director’s Office at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Her experience at the Studio Museum in Harlem inspired her work on social media with a blog she started writing in 2011 called “Black Contemporary Art”, a Tumblr blog where she posts art by and about people of African descent to share with online viewers. She also featured many posts from other contributors on artwork made by and about people of African descent. I visited her Tumblr blog, and it has an interesting mix of artwork in various mediums including photography and paintings depicting people of African descent. One of the pieces that caught my attention was Charles McGee’s Noah’s Ark: Genesis (1984), posted on April 5th and was made with enamel and mixed media on masonic; it caught my attention because it has numerous prints mixed together, limited colors that stick out from the rest of the piece, and these features provide an interesting interpretation of the story of Noah’s Ark. Her blog was what inspired her interest in social media.

After beginning her blog, Drew has worked for Hyperallergic, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and Lehmann Maupin. Then she gave lectures and participated in panel discussions at places such as the New Museum, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the Brooklyn Museum. Drew was honored by AIR Gallery as the recipient of their inaugural Feminist Curator Award, was selected as one of the YBCA100 by the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and selected as one of Brooklyn Magazine’s Brooklyn 100. Another question that was asked was what were the challenges in working in the digital platform.

Drew explained that in her role as Social Media Manager at the Met the strategy for digital access for the Met constantly change. She also points out, that in addition to pointing out the challenges, she enjoys her work in adapting materials to make them more accessible for various people of limited abilities. Also, Drew discussed that a line must be drawn between being glued to the computer and “unplugging”; in other words, one managing social media has to find ways to not make working on social media taxing. This I understand because it is important to access resources shared on social media but there are so many things on the Internet that it can be easy to end up glued to the computer or laptop. I myself use social media to keep up to date on resources I see from various museums and museum associations and to maintain networks made on the social media sites; what I usually do to find a balance of spending time away from social media and on social media is I dedicate time to look through social media sites to see what has been posted, then I saved what captured my attention and move on to other aspects in life away from the computer.

Drew moved on to the topic on the future of museums and communities. She stated that museums should be encouraged to continue connecting with the community outside of the museum. Drew also stressed the importance of reaching out to community leaders, and to bridge dialogue with the community through social media outlets. Initiating dialogue goes a long way for making people aware of what organizations such as historic house museums and art institutions offer since it is easy for people to forget about their existence even when they live near these places. I agree that it is significant to maintain a strong relationship with the community because it helps support museums importance within the community and maintaining museums as resources communities can turn to. When museums maintain and update their social media outlets such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, people understand what museums have to offer in terms of programming and resources they can participate in and use. For instance, I continue to learn more about museums on Long Island by following them on their Facebook pages.

After the discussion opened to questions from the audience in the center, one of the questions asked was what projects inspires Drew and brings her joy. She did not point to a specific project but she stated that she likes people and she is happy to be able to talk to many people and hear different perspectives. I see where she is coming from because since getting more involved in social media myself and creating this blog I have met so many people and learned a lot from them on their experiences and perspectives in the field; I appreciate all the responses to the blog, and thank you all for continuing to inspire me to continue to write. Drew also said that she likes walking to the Met each day and notice people take selfies and share them on the social media sites since she sees so many different stories and perspectives in each one. This further points out that people’s experiences in museums vary from person to person, and different aspects of museums make an impact in various ways. Museums continue to serve the community, and we need to continue social media to adapt to an evolving society.

How does your organization use social media? What are the challenges you face on social media?

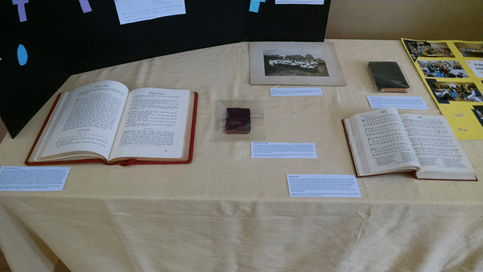

Some of the items selected for the exhibit.

Some of the items selected for the exhibit. Picture of exhibit board designed using limited resources.

Picture of exhibit board designed using limited resources. The exhibit as a whole. Trinity Traditions: Easter Celebrations Throughout the Century.

The exhibit as a whole. Trinity Traditions: Easter Celebrations Throughout the Century. Museum of Chinese in America

Museum of Chinese in America

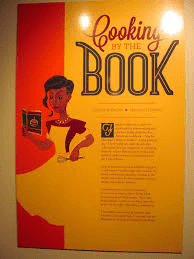

Since then I did not see much of the history of food presented in a museum setting until I came across Michelle Moon’s Interpreting Food in Museums and Historic Sites which was published by the American Association of State and Local History in 2015, and the basis of this past week’s American Association of State and Local History (AASLH) webinar. Moon’s book argued that museums and historic sites have an opportunity to draw new audiences and infuse new meaning into their food presentations, and food deserves a central place in historic interpretation. Her book provides the framework for understanding big ideas in food history, suggesting best practices for linking objects, exhibits and demonstrations with the larger story of change in food production as well as consumption over the past two centuries. She also argues that food tells a story in which visitors can see themselves, and explore their own relationships to food.

Since then I did not see much of the history of food presented in a museum setting until I came across Michelle Moon’s Interpreting Food in Museums and Historic Sites which was published by the American Association of State and Local History in 2015, and the basis of this past week’s American Association of State and Local History (AASLH) webinar. Moon’s book argued that museums and historic sites have an opportunity to draw new audiences and infuse new meaning into their food presentations, and food deserves a central place in historic interpretation. Her book provides the framework for understanding big ideas in food history, suggesting best practices for linking objects, exhibits and demonstrations with the larger story of change in food production as well as consumption over the past two centuries. She also argues that food tells a story in which visitors can see themselves, and explore their own relationships to food.