Added to Medium, September 27, 2017

This week I am posting earlier than usual because I have a family event this weekend I am preparing for and I also want to address a blog post from Alliance Labs, the American Alliance of Museums blog, discussing the topic of why many museum professionals are leaving the field.

It is an important topic because there are so many people considering leaving the field for various reasons, and we need to do something to work towards making our field more inclusive and rewarding for museum professionals to make it more appealing to stay. After reading this blog and similar articles, the experience made me think about my own reasoning for staying in the field as well as my resolve to be a part of making this museum field a more encouraging field to continue working in.

Sarah Erdman, Claudia Ocello, Dawn Estabrooks Salerno, and Marieke Van Damme last week talked about this topic in their blog “Leaving the Museum Field”. These four museum professionals got together after the 2016 AAM conference in DC to try to find out the reasons museum workers leave the field. In this blog, they presented their findings based on the over one thousand individuals who participated in a survey with open-ended questions. One of the questions that were placed in the survey include,

“Why we stay. Hands down, we stay because of the work we do. Unsurprisingly, for those of us who have made lifelong friends at our museums, we also stay because of our coworkers. The close 3rd and 4th reasons for staying are “Pay/Benefits” and “No Other Option.” The least popular response was “Feel Lucky to Have a Job” (1%) and the write-in “I love dinosaurs.”’

I have mentioned in previous blog posts my reasons for joining the museum field, and for me my reasons are definitely for the love of the work I do as well as my passion for museums. In my very first blog post, “Writing about Museum Education”, I mentioned my family trips to museums inspired my passion for and my career in museum education. I also pointed out that

“Education for me has always been my favorite part of life, and while at times it was challenging for me field trips especially to museums have given me a way to understand the lessons I learned in the classroom.”

I still believe museums can illuminate an individual’s educational experience, and by continuing in the museum field I hope to make an impact on the public. It is a challenge to accomplish this when there are things that prevent me from fulfilling this goal.

As I was graduating with my Master’s degree in Public History, there were limited opportunities to get a position in the field that would meet the typical needs. Similar limitations were addressed in the blog post as reasons museum professionals are leaving. According to the blog,

“Reasons why museum workers leave the field. We had about 300 answers to this open-ended question. We grouped them by theme and found the following reasons (in order of frequency of response):

1. Pay was too low

2. Other

3. Poor work/life balance

4. Insufficient benefits

5. [tie] Workload/Better positions

6. Schedule didn’t work.”

There was a point that I thought I should consider leaving. However, I thought about my experiences I have had at this point, and knew there is so much I still have to offer to the field. I began working at the Maritime Explorium, a children’s science museum, which is a little different from my previous experiences but is just as passionate about education for children and the public as I am. Also, I began work on this blog sharing my experiences in the museum field as well as my impressions on current trends in the field. I also became involved in museum organizations, including the Gender Equity in Museums Movement, to help other museums and museum professionals make a difference in the community and within their institutions.

In a way, I adapted my career in the museum education field and I found a way to stay in the field. I continue to work hard to stay in the field. This blog pointed out a number of ways to help museum professionals stay; it stated,

“How can we prevent museum workers from leaving? Again, increasing pay was at the top of the list, but respondents also suggested many free or cost-effective ways to create better working environments, like:

Create mentoring opportunities

Respect each other – break departmental silos

Make room for new ideas.”

By following the previously mentioned suggestions, we as museum professionals will be able to work towards making museums a better workforce to stay in so we would be able to work within our communities better.

While I continue to face challenges in attaining these needs, I am thankful for every opportunity that I have experienced in the field. Each experience has led me to getting to know various people in the field and to learning lessons in the field that help me grow as a museum professional.

The key to making this field a more appealing field to stay in is to keep working towards making a change in our museums and the museum community. It would not be realistic to expect the museum field to be better overnight. We need to keep talking about this situation, and be able to learn from this experience to move forward. I included the original link to the blog in my resources section for all museum professionals to refer to, and it also includes a variety of resources related to this topic to refer to.

Please leave your responses about this topic on my blog and/or the Alliance Labs blog, and continue this discussion among your colleagues.

Resources:

http://labs.aam-us.org/blog/leaving-the-museum-field/

https://www.genderequitymuseums.com/

Connecticut Historical Society, pen, drawn 2015

Connecticut Historical Society, pen, drawn 2015 Noah Webster House, pen, drawn 2015

Noah Webster House, pen, drawn 2015 Stanley-Whitman House, pen, drawn 2014

Stanley-Whitman House, pen, drawn 2014 Butler-McCook House, pencil, drawn 2014

Butler-McCook House, pencil, drawn 2014 Norris, Linda and Rainey Tisdale, Creativity in Museum Practice, Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2014.

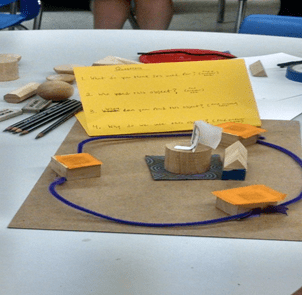

Norris, Linda and Rainey Tisdale, Creativity in Museum Practice, Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2014. “Exhibition Designs for Educators” Activity, October 2016

“Exhibition Designs for Educators” Activity, October 2016 Summertime Fun with Trinity exhibit, opened June 4, 2017

Summertime Fun with Trinity exhibit, opened June 4, 2017